Lymphatic system

| Lymphatic system | |

|---|---|

Human lymphatic system | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | systema lymphoideum |

| MeSH | D008208 |

| TA98 | A13.0.00.000 |

| TA2 | 5149 |

| FMA | 7162 74594, 7162 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

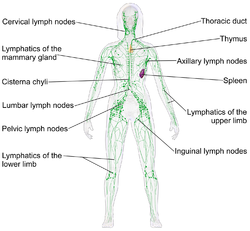

The lymphatic system, or lymphoid system, is an organ system in vertebrates that is part of the immune system and complementary to the circulatory system. It consists of a large network of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, lymphoid organs, lymphatic tissue and lymph.[1][2] Lymph is a clear fluid carried by the lymphatic vessels back to the heart for re-circulation. The Latin word for lymph, lympha, refers to the deity of fresh water, "Lympha".[3]

Unlike the circulatory system that is a closed system, the lymphatic system is open.[4][5] The human circulatory system processes an average of 20 litres of blood per day through capillary filtration, which removes plasma from the blood. Roughly 17 litres of the filtered blood is reabsorbed directly into the blood vessels, while the remaining three litres are left in the interstitial fluid. One of the main functions of the lymphatic system is to provide an accessory return route to the blood for the surplus three litres.[6]

The other main function is that of immune defense. Lymph is very similar to blood plasma, in that it contains waste products and cellular debris, together with bacteria and proteins. The cells of the lymph are mostly lymphocytes. Associated lymphoid organs are composed of lymphoid tissue, and are the sites either of lymphocyte production or of lymphocyte activation. These include the lymph nodes (where the highest lymphocyte concentration is found), the spleen, the thymus, and the tonsils. Lymphocytes are initially generated in the bone marrow. The lymphoid organs also contain other types of cells such as stromal cells for support.[7] Lymphoid tissue is also associated with mucosas such as mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT).[8]

Fluid from circulating blood leaks into the tissues of the body by capillary action, carrying nutrients to the cells. The fluid bathes the tissues as interstitial fluid, collecting waste products, bacteria, and damaged cells, and then drains as lymph into the lymphatic capillaries and lymphatic vessels. These vessels carry the lymph throughout the body, passing through numerous lymph nodes which filter out unwanted materials such as bacteria and damaged cells. Lymph then passes into much larger lymph vessels known as lymph ducts. The right lymphatic duct drains the right side of the region and the much larger left lymphatic duct, known as the thoracic duct, drains the left side of the body. The ducts empty into the subclavian veins to return to the blood circulation. Lymph is moved through the system by muscle contractions.[9] In some vertebrates, a lymph heart is present that pumps the lymph to the veins.[9][10]

The lymphatic system was first described in the 17th century independently by Olaus Rudbeck and Thomas Bartholin.[11]

Structure

[edit]

The lymphatic system consists of a conducting network of lymphatic vessels, lymphoid organs, lymphoid tissues, and the circulating lymph.[1]

Primary lymphoid organs

[edit]The primary (or central) lymphoid organs, including the thymus, bone marrow, fetal liver and yolk sac, are responsible for generating lymphocytes from immature progenitor cells in the absence of antigens.[12] The thymus and the bone marrow constitute the primary lymphoid organs involved in the production and early clonal selection of lymphocyte tissues.

Avian species's primary lymphoid organs include the bone marrow, thymus, bursa of Fabricius, and yolk sac.[13]

Bone marrow

[edit]Bone marrow is responsible for both the creation of T cell precursors and the production and maturation of B cells, which are important cell types of the immune system. From the bone marrow, B cells immediately join the circulatory system and travel to secondary lymphoid organs in search of pathogens. T cells, on the other hand, travel from the bone marrow to the thymus, where they develop further and mature. Mature T cells then join B cells in search of pathogens. The other 95% of T cells begin a process of apoptosis, a form of programmed cell death.

Thymus

[edit]The thymus increases in size from birth in response to postnatal antigen stimulation. It is most active during the neonatal and pre-adolescent periods. The thymus is located between the inferior neck and the superior thorax. At puberty, by the early teens, the thymus begins to atrophy and regress, with adipose tissue mostly replacing the thymic stroma. However, residual T cell lymphopoiesis continues throughout adult life, providing some immune response. The thymus is where the T lymphocytes mature and become immunocompetent. The loss or lack of the thymus results in severe immunodeficiency and subsequent high susceptibility to infection. In most species, the thymus consists of lobules divided by septa which are made up of epithelium which is often considered an epithelial organ. T cells mature from thymocytes, proliferate, and undergo a selection process in the thymic cortex before entering the medulla to interact with epithelial cells.

Research on bony fish showed a buildup of T cells in the thymus and spleen of lymphoid tissues in salmon and showed that there are not many T cells in non-lymphoid tissues.[14]

The thymus provides an inductive environment for the development of T cells from hematopoietic progenitor cells. In addition, thymic stromal cells allow for the selection of a functional and self-tolerant T cell repertoire. Therefore, one of the most important roles of the thymus is the induction of central tolerance. However, the thymus is not where the infection is fought, as the T cells have yet to become immunocompetent.

Secondary lymphoid organs

[edit]The secondary (or peripheral) lymphoid organs, which include lymph nodes and the spleen, maintain mature naive lymphocytes and initiate an adaptive immune response.[15] The secondary lymphoid organs are the sites of lymphocyte activation by antigens.[16] Activation leads to clonal expansion, and affinity maturation. Mature lymphocytes recirculate between the blood and the secondary lymphoid organs until they encounter their specific antigen.

Spleen

[edit]The main functions of the spleen are:

- to produce immune cells to fight antigens

- to remove particulate matter and aged blood cells, mainly red blood cells

- to produce blood cells during fetal life.

The spleen synthesizes antibodies in its white pulp and removes antibody-coated bacteria and antibody-coated blood cells by way of blood and lymph node circulation. The white pulp of the spleen provides immune function due to the lymphocytes that are housed there. The spleen also consists of red pulp which is responsible for getting rid of aged red blood cells, as well as pathogens. This is carried out by macrophages present in the red pulp. A study published in 2009 using mice found that the spleen contains, in its reserve, half of the body's monocytes within the red pulp.[17] These monocytes, upon moving to injured tissue (such as the heart), turn into dendritic cells and macrophages while promoting tissue healing.[17][18][19] The spleen is a center of activity of the mononuclear phagocyte system and can be considered analogous to a large lymph node, as its absence causes a predisposition to certain infections. Notably, the spleen is important for a multitude of functions. The spleen removes pathogens and old erythrocytes from the blood (red pulp) and produces lymphocytes for immune response (white pulp). The spleen also is responsible for recycling some erythrocytes components and discarding others. For example, hemoglobin is broken down into amino acids that are reused.

Research on bony fish has shown that a high concentration of T cells are found in the white pulp of the spleen.[14]

Like the thymus, the spleen has only efferent lymphatic vessels. Both the short gastric arteries and the splenic artery supply it with blood.[20] The germinal centers are supplied by arterioles called penicilliary radicles.[21]

In the human until the fifth month of prenatal development, the spleen creates red blood cells; after birth, the bone marrow is solely responsible for hematopoiesis. As a major lymphoid organ and a central player in the reticuloendothelial system, the spleen retains the ability to produce lymphocytes. The spleen stores red blood cells and lymphocytes. It can store enough blood cells to help in an emergency. Up to 25% of lymphocytes can be stored at any one time.[22]

Lymph nodes

[edit]

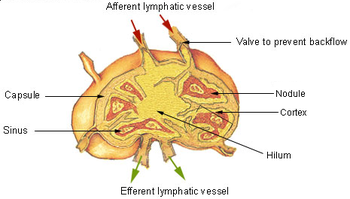

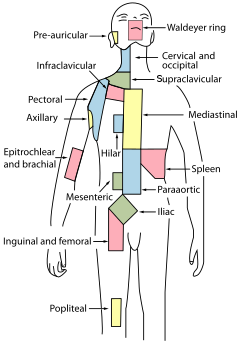

A lymph node is an organized collection of lymphoid tissue, through which the lymph passes on its way back to the blood. Lymph nodes are located at intervals along the lymphatic system. Several afferent lymph vessels bring in lymph, which percolates through the substance of the lymph node, and is then drained out by an efferent lymph vessel. Of the nearly 800 lymph nodes in the human body, about 300 are located in the head and neck.[23] Many are grouped in clusters in different regions, as in the underarm and abdominal areas. Lymph node clusters are commonly found at the proximal ends of limbs (groin, armpits) and in the neck, where lymph is collected from regions of the body likely to sustain pathogen contamination from injuries. Lymph nodes are particularly numerous in the mediastinum in the chest, neck, pelvis, axilla, inguinal region, and in association with the blood vessels of the intestines.[8]

The substance of a lymph node consists of lymphoid follicles in an outer portion called the cortex. The inner portion of the node is called the medulla, which is surrounded by the cortex on all sides except for a portion known as the hilum. The hilum presents as a depression on the surface of the lymph node, causing the otherwise spherical lymph node to be bean-shaped or ovoid. The efferent lymph vessel directly emerges from the lymph node at the hilum. The arteries and veins supplying the lymph node with blood enter and exit through the hilum. The region of the lymph node called the paracortex immediately surrounds the medulla. Unlike the cortex, which has mostly immature T cells, or thymocytes, the paracortex has a mixture of immature and mature T cells. Lymphocytes enter the lymph nodes through specialised high endothelial venules found in the paracortex.

A lymph follicle is a dense collection of lymphocytes, the number, size, and configuration of which change in accordance with the functional state of the lymph node. For example, the follicles expand significantly when encountering a foreign antigen. The selection of B cells, or B lymphocytes, occurs in the germinal centre of the lymph nodes.

Secondary lymphoid tissue provides the environment for the foreign or altered native molecules (antigens) to interact with the lymphocytes. It is exemplified by the lymph nodes, and the lymphoid follicles in tonsils, Peyer's patches, spleen, adenoids, skin, etc. that are associated with the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT).

In the gastrointestinal wall, the appendix has mucosa resembling that of the colon, but here it is heavily infiltrated with lymphocytes.

Tertiary lymphoid organs

[edit]Tertiary lymphoid organs (TLOs) are abnormal lymph node-like structures that form in peripheral tissues at sites of chronic inflammation, such as chronic infection, transplanted organs undergoing graft rejection, some cancers, and autoimmune and autoimmune-related diseases.[24] TLOs are often characterized by CD20+ B cell zone which is surrounded by CD3+ T cell zone, similar to the lymph follicles in secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs) and are regulated differently from the normal process whereby lymphoid tissues are formed during ontogeny, being dependent on cytokines and hematopoietic cells, but still drain interstitial fluid and transport lymphocytes in response to the same chemical messengers and gradients.[25][26] Mature TLOs often have an active germinal center, surrounded by a network of follicular dendritic cells (FDCs).[27] Although the specific composition of TLSs may vary, within the T cell compartment, the dominant subset of T cells is CD4+ T follicular helper (TFH) cells, but certain number of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, CD4+ T helper 1 (TH1) cells, and regulatory T cells (Tregs) can also be found within the T cell zone.[25] The B cell zone contains two main areas. The mantle is located at the periphery and composed of naive immunoglobulin D (IgD)+ B cells surrounding the germinal centre. The latter is defined by the presence of proliferating Ki67+CD23+ B cells and a CD21+ FDC network, as observed in SLOs.[28] TLOs typically contain far fewer lymphocytes, and assume an immune role only when challenged with antigens that result in inflammation. They achieve this by importing the lymphocytes from blood and lymph.[29]

According to the composition and activation status of the cells within the lymphoid structures, at least three organizational levels of TLOs have been described. The formation of TLOs starts with the aggregating of lymphoid cells and occasional DCs but FDCs are lacking at this stage. The next stage is immature TLOs, also known as primary follicle-like TLS, which have increased number of T cells and B cells with distinct T cell and B cell zones as well as the formation of FDCs network, but without germinal centres. Finally, fully mature (also known as secondary follicle-like) TLOs often have active germinal centres and high endothelial venules(HEVs), demonstrating a functional capacity by promoting T cell and B cell activation then leading to expansion of TLS through cell proliferation and recruitment. During TLS formation, T cells and B cells are separated into two different but adjacent zones, with some cells having the ability to migrate from one to the other, which is a crucial step in the development of an effective and coordinated immune response.[28][30]

TLOs are now being identified to have an important role in the immune response to cancer and to be a prognostic marker for immunotherapy. TLOs have been reported to present in different cancer types such as melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer and colorectal cancer (reviewed in [31]) as well as glioma.[32] TLOs are also been seen as a read-out of treatment efficacy. For example, in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), vaccination led to formation of TLOs in responders. Within these patients, lymphocytes in TLOs displayed an activated phenotype and in vitro experiments showed their capacity to perform effector functions.[28] Patients with the presence of TLOs tend to have a better prognosis,[33][34] even though some certain cancer types showed an opposite effect.[35] Besides, TLOs that with an active germinal center seem to show a better prognosis than those with TLOs without a germinal center.[33][34] The reason that these patients tend to live longer is that immune response against tumor can be promoted by TLOs. TLOs may also enhance anti-tumor response when patients are treated with immunotherapy such as immune checkpoint blockade treatment.[36]

Other lymphoid tissue

[edit]Lymphoid tissue associated with the lymphatic system is concerned with immune functions in defending the body against infections and the spread of tumours. It consists of connective tissue formed of reticular fibers, with various types of leukocytes (white blood cells), mostly lymphocytes enmeshed in it, through which the lymph passes.[37] Regions of the lymphoid tissue that are densely packed with lymphocytes are known as lymphoid follicles. Lymphoid tissue can either be structurally well organized as lymph nodes or may consist of loosely organized lymphoid follicles known as the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT).

The central nervous system also has lymphatic vessels. The search for T cell gateways into and out of the meninges uncovered functional meningeal lymphatic vessels lining the dural sinuses, anatomically integrated into the membrane surrounding the brain.[38]

Lymphatic vessels

[edit]

The lymphatic vessels, also called lymph vessels, are thin-walled vessels that conduct lymph between different parts of the body.[39] They include the tubular vessels of the lymph capillaries, and the larger collecting vessels – the right lymphatic duct and the thoracic duct (the left lymphatic duct). The lymph capillaries are mainly responsible for the absorption of interstitial fluid from the tissues, while lymph vessels propel the absorbed fluid forward into the larger collecting ducts, where it ultimately returns to the bloodstream via one of the subclavian veins.

The tissues of the lymphatic system are responsible for maintaining the balance of the body fluids. Its network of capillaries and collecting lymphatic vessels work to efficiently drain and transport extravasated fluid, along with proteins and antigens, back to the circulatory system. Numerous intraluminal valves in the vessels ensure a unidirectional flow of lymph without reflux.[40] Two valve systems, a primary and a secondary valve system, are used to achieve this unidirectional flow.[41] The capillaries are blind-ended, and the valves at the ends of capillaries use specialised junctions together with anchoring filaments to allow a unidirectional flow to the primary vessels. When interstitial fluid increases, it causes swelling that stretches collagen fibers anchored to adjacent connective tissue, in turn opening the unidirectional valves at the ends of these capillaries, facilitating the entry and subsequent drainage of excess lymph fluid. The collecting lymphatics, however, act to propel the lymph by the combined actions of the intraluminal valves and lymphatic muscle cells.[42]

Development

[edit]Lymphatic tissues begin to develop by the end of the fifth week of embryonic development.

Lymphatic vessels develop from lymph sacs that arise from developing veins, which are derived from mesoderm.

The first lymph sacs to appear are the paired jugular lymph sacs at the junction of the internal jugular and subclavian veins.

From the jugular lymph sacs, lymphatic capillary plexuses spread to the thorax, upper limbs, neck, and head.

Some of the plexuses enlarge and form lymphatic vessels in their respective regions. Each jugular lymph sac retains at least one connection with its jugular vein, the left one developing into the superior portion of the thoracic duct.

The spleen develops from mesenchymal cells between layers of the dorsal mesentery of the stomach.

The thymus arises as an outgrowth of the third pharyngeal pouch.

Function

[edit]The lymphatic system has multiple interrelated functions:[43][44][45][46][47][48][49]

- It is responsible for the removal of interstitial fluid from tissues

- It absorbs and transports fatty acids and fats as chyle from the digestive system

- It transports white blood cells to and from the lymph nodes into the bones

- The lymph transports antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells, to the lymph nodes where an immune response is stimulated.

Fat absorption

[edit]

Lymph vessels called lacteals are at the beginning of the gastrointestinal tract, predominantly in the small intestine. While most other nutrients absorbed by the small intestine are passed on to the portal venous system to drain via the portal vein into the liver for processing, fats (lipids) are passed on to the lymphatic system to be transported to the blood circulation via the thoracic duct. (There are exceptions, for example medium-chain triglycerides are fatty acid esters of glycerol that passively diffuse from the GI tract to the portal system.) The enriched lymph originating in the lymphatics of the small intestine is called chyle. The nutrients that are released into the circulatory system are processed by the liver, having passed through the systemic circulation.

Immune function

[edit]The lymphatic system plays a major role in the body's immune system, as the primary site for cells relating to adaptive immune system including T-cells and B-cells.

Cells in the lymphatic system react to antigens presented or found by the cells directly or by other dendritic cells.

When an antigen is recognized, an immunological cascade begins involving the activation and recruitment of more and more cells, the production of antibodies and cytokines and the recruitment of other immunological cells such as macrophages.

Clinical significance

[edit]The study of lymphatic drainage of various organs is important in the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of cancer. The lymphatic system, because of its closeness to many tissues of the body, is responsible for carrying cancerous cells between the various parts of the body in a process called metastasis. The intervening lymph nodes can trap the cancer cells. If they are not successful in destroying the cancer cells the nodes may become sites of secondary tumours.

[50] The lymphatic system (LS) comprises lymphoid organs and a network of vessels responsible for transporting interstitial fluid, antigens, lipids, cholesterol, immune cells, and other materials throughout the body. Dysfunction or abnormal development of the LS has been linked to numerous diseases, making it critical for fluid balance, immune cell trafficking, and inflammation control. Recent advancements, including single-cell technologies, clinical imaging, and biomarker discovery, have improved the ability to study and understand the LS, providing potential pathways for disease prevention and treatment. Studies have shown that the lymphatic system also plays a role in modulating immune responses, with dysfunction linked to chronic inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, as well as cancer progression.

Enlarged lymph nodes

[edit]Lymphadenopathy refers to one or more enlarged lymph nodes. Small groups or individually enlarged lymph nodes are generally reactive in response to infection or inflammation. This is called local lymphadenopathy. When many lymph nodes in different areas of the body are involved, this is called generalised lymphadenopathy. Generalised lymphadenopathy may be caused by infections such as infectious mononucleosis, tuberculosis and HIV, connective tissue diseases such as SLE and rheumatoid arthritis, and cancers, including both cancers of tissue within lymph nodes, discussed below, and metastasis of cancerous cells from other parts of the body, that have arrived via the lymphatic system.[51][52]

Lymphedema

[edit]Lymphedema is the swelling caused by the accumulation of lymph, which may occur if the lymphatic system is damaged or has malformations. It usually affects limbs, though the face, neck and abdomen may also be affected. In an extreme state, called elephantiasis, the edema progresses to the extent that the skin becomes thick with an appearance similar to the skin on elephant limbs.[53]

Causes are unknown in most cases, but sometimes there is a previous history of severe infection, usually caused by a parasitic disease, such as lymphatic filariasis.

Lymphangiomatosis is a disease involving multiple cysts or lesions formed from lymphatic vessels.[relevant to this paragraph? – discuss]

Lymphedema can also occur after surgical removal of lymph nodes in the armpit (causing the arm to swell due to poor lymphatic drainage) or groin (causing swelling of the leg). Conventional treatment is by manual lymphatic drainage and compression garments. Two drugs for the treatment of lymphedema are in clinical trials: Lymfactin[54] and Ubenimex/Bestatin. There is no evidence to suggest that the effects of manual lymphatic drainage are permanent.[55]

Cancer

[edit]

Cancer of the lymphatic system can be primary or secondary. Lymphoma refers to cancer that arises from lymphatic tissue. Lymphoid leukaemias and lymphomas are now considered to be tumours of the same type of cell lineage. They are called "leukaemia" when in the blood or marrow and "lymphoma" when in lymphatic tissue. They are grouped together under the name "lymphoid malignancy".[56]

Lymphoma is generally considered as either Hodgkin lymphoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Hodgkin lymphoma is characterised by a particular type of cell, called a Reed–Sternberg cell, visible under microscope. It is associated with past infection with the Epstein–Barr virus, and generally causes a painless "rubbery" lymphadenopathy. It is staged, using Ann Arbor staging. Chemotherapy generally involves the ABVD and may also involve radiotherapy.[51] Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is a cancer characterised by increased proliferation of B-cells or T-cells, generally occurs in an older age group than Hodgkin lymphoma. It is treated according to whether it is high-grade or low-grade, and carries a poorer prognosis than Hodgkin lymphoma.[51]

Lymphangiosarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumour, whereas lymphangioma is a benign tumour occurring frequently in association with Turner syndrome. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis is a benign tumour of the smooth muscles of the lymphatics that occurs in the lungs.

Lymphoid leukaemia is another form of cancer where the host is devoid of different lymphatic cells.

Other

[edit]History

[edit]Hippocrates, in the 5th century BC, was one of the first people to mention the lymphatic system. In his work On Joints, he briefly mentioned the lymph nodes in one sentence. Rufus of Ephesus, a Roman physician, identified the axillary, inguinal and mesenteric lymph nodes as well as the thymus during the 1st to 2nd century AD.[57] The first mention of lymphatic vessels was in the 3rd century BC by Herophilos, a Greek anatomist living in Alexandria, who incorrectly concluded that the "absorptive veins of the lymphatics," by which he meant the lacteals (lymph vessels of the intestines), drained into the hepatic portal veins, and thus into the liver.[57] The findings of Ruphus and Herophilos were further propagated by the Greek physician Galen, who described the lacteals and mesenteric lymph nodes which he observed in his dissection of apes and pigs in the 2nd century AD.[57]

In the mid 16th century, Gabriele Falloppio (discoverer of the fallopian tubes), described what is now known as the lacteals as "coursing over the intestines full of yellow matter."[57] In about 1563 Bartolomeo Eustachi, a professor of anatomy, described the thoracic duct in horses as vena alba thoracis.[57] The next breakthrough came when in 1622 a physician, Gaspare Aselli, identified lymphatic vessels of the intestines in dogs and termed them venae albae et lacteae, which are now known as simply the lacteals. The lacteals were termed the fourth kind of vessels (the other three being the artery, vein and nerve, which was then believed to be a type of vessel), and disproved Galen's assertion that chyle was carried by the veins. But, he still believed that the lacteals carried the chyle to the liver (as taught by Galen).[58] He also identified the thoracic duct but failed to notice its connection with the lacteals.[57] This connection was established by Jean Pecquet in 1651, who found a white fluid mixing with blood in a dog's heart. He suspected that fluid to be chyle as its flow increased when abdominal pressure was applied. He traced this fluid to the thoracic duct, which he then followed to a chyle-filled sac he called the chyli receptaculum, which is now known as the cisternae chyli; further investigations led him to find that lacteals' contents enter the venous system via the thoracic duct.[57][58] Thus, it was proven convincingly that the lacteals did not terminate in the liver, thus disproving Galen's second idea: that the chyle flowed to the liver.[58] Johann Veslingius drew the earliest sketches of the lacteals in humans in 1641.[59]

The idea that blood recirculates through the body rather than being produced anew by the liver and the heart was first accepted as a result of works of William Harvey—a work he published in 1628. In 1652, Olaus Rudbeck (1630–1702) discovered certain transparent vessels in the liver that contained clear fluid (and not white), and thus named them hepatico-aqueous vessels. He also learned that they emptied into the thoracic duct and that they had valves.[58] He announced his findings in the court of Queen Christina of Sweden, but did not publish his findings for a year,[60] and in the interim similar findings were published by Thomas Bartholin, who additionally published that such vessels are present everywhere in the body, not just in the liver. He is also the one to have named them "lymphatic vessels."[58] This had resulted in a bitter dispute between one of Bartholin's pupils, Martin Bogdan,[61] and Rudbeck, whom he accused of plagiarism.[60]

Galen's ideas prevailed in medicine until the 17th century. It was thought that blood was produced by the liver from chyle contaminated with ailments by the intestine and stomach, to which various spirits were added by other organs, and that this blood was consumed by all the organs of the body. This theory required that the blood be consumed and produced many times over. Even in the 17th century, his ideas were defended by some physicians.[62][63][64]

Alexander Monro, of the University of Edinburgh Medical School, was the first to describe the function of the lymphatic system in detail.[65]

UVA School of Medicine researchers Jonathan Kipnis and Antoine Louveau discovered previously unknown vessels connecting the human brain directly to the lymphatic system. The discovery "redrew the map" of the lymphatic system, rewrote medical textbooks, and struck down long-held beliefs about how the immune system functions in the brain. The discovery may help greatly in combating neurological diseases from multiple sclerosis to Alzheimer's disease.[66]

-

"Claude Galien". Lithograph by Pierre Roche Vigneron. (Paris: Lith de Gregoire et Deneux, c. 1865)

-

Portrait of Eustachius

-

Olaus Rudbeck in 1696.

Etymology

[edit]Lymph originates in the Classical Latin word lympha "water",[67] which is also the source of the English word limpid. The spelling with y and ph was influenced by folk etymology with Greek νύμϕη (nýmphē) "nymph".[68]

The adjective used for the lymph-transporting system is lymphatic. The adjective used for the tissues where lymphocytes are formed is lymphoid. Lymphatic comes from the Latin word lymphaticus, meaning "connected to water."

See also

[edit]- List of lymphatic nodes of the human body

- American Society of Lymphology

- Glymphatic system and Meningeal lymphatic vessels - equivalent for the central nervous system

- Innate lymphoid cells

- Lymphangiogenesis

- Lymphangion

- Mononuclear phagocyte system

- Waldemar Olszewski – discovered fundamental processes in human tissues connected with function of the lymphatic system

- Trogocytosis

References

[edit]- ^ a b Standring S (2016). Gray's anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice (Forty-first ed.). Elsevier Limited. pp. 68–73. ISBN 9780702052309.

- ^ Moore K (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy (Eighth ed.). Wolters Kluwer. pp. 43–45. ISBN 9781496347213.

- ^ Natale G, Bocci G, Ribatti D (September 2017). "Scholars and scientists in the history of the lymphatic system". Journal of Anatomy. 231 (3): 417–429. doi:10.1111/joa.12644. PMC 5554832. PMID 28614587.

- ^ Zhang, Yufan; Zhang, Juxiang; Li, Xiaowei; Li, Jingru; Lu, Shuting; Li, Yuqiao; Ren, Panting; Zhang, Chunfu; Xiong, Liqin (2022-06-01). "Imaging of fluorescent polymer dots in relation to channels and immune cells in the lymphatic system". Materials Today Bio. 15: 100317. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100317. ISSN 2590-0064. PMC 9213818. PMID 35757035.

- ^ Hu, Dan; Li, Long; Li, Sufang; Wu, Manyan; Ge, Nana; Cui, Yuxia; Lian, Zheng; Song, Junxian; Chen, Hong (2019-08-01). "Lymphatic system identification, pathophysiology and therapy in the cardiovascular diseases". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 133: 99–111. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.06.002. ISSN 0022-2828. PMID 31181226. S2CID 184485255.

- ^ Sherwood L (January 1, 2012). Human Physiology: From Cells to Systems. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781111577438 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mak TW, Saunders ME, Saunders ME (2008). Primer to the immune response. Academic Press. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-12-374163-9. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ a b Warwick R, Williams PL. "Angiology (Chapter 6)". Gray's anatomy (Thirty-fifth ed.). London: Longman. pp. 588–785.

- ^ a b Peyrot SM, Martin BL, Harland RM (March 2010). "Lymph heart musculature is under distinct developmental control from lymphatic endothelium". Developmental Biology. 339 (2): 429–38. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.01.002. PMC 2845526. PMID 20067786.

- ^ Jeltsch M, Tammela T, Alitalo K, Wilting J (October 2003). "Genesis and pathogenesis of lymphatic vessels". Cell and Tissue Research. 314 (1): 69–84. doi:10.1007/s00441-003-0777-2. PMID 12942362. S2CID 23318096.

- ^ Eriksson G (2004). "[Olaus Rudbeck as scientist and professor of medicine]". Svensk Medicinhistorisk Tidskrift. 8 (1): 39–44. PMID 16025602.

- ^ Flajnik, Martin F.; Singh, Nevil J.; Holland, Steven M., eds. (2023). "CHAPTER 8 Lymphoid tissues and organs". Paul's fundamental immunology (8th ed.). Philadelphia Baltimore New York London Buenos Aires Hong Kong Sydney Tokyo: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-9751-4253-7.

- ^ Pendl •, Helene; Tizard, Ian (2016), "Immunology", Current Therapy in Avian Medicine and Surgery, Elsevier, pp. 400–432, doi:10.1016/b978-1-4557-4671-2.00020-3, ISBN 978-1-4557-4671-2, retrieved 2024-08-28

- ^ a b Koppang EO, Fischer U, Moore L, Tranulis MA, Dijkstra JM, Köllner B, Aune L, Jirillo E, Hordvik I (December 2010). "Salmonid T cells assemble in the thymus, spleen and in novel interbranchial lymphoid tissue". J Anat. 217 (6): 728–39. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01305.x. PMC 3039185. PMID 20880086.

- ^ Ruddle NH, Akirav EM (August 2009). "Secondary lymphoid organs: responding to genetic and environmental cues in ontogeny and the immune response". Journal of Immunology. 183 (4): 2205–12. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0804324. PMC 2766168. PMID 19661265.

- ^ Ruddle, N. H.; Akirav, E. M. (2009). "Secondary Lymphoid Organs: Responding to Genetic and Environmental Cues in Ontogeny and the Immune Response1". Journal of Immunology. 183 (4): 2205–2212. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0804324. PMC 2766168. PMID 19661265.

- ^ a b Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M, Etzrodt M, Wildgruber M, Cortez-Retamozo V, Panizzi P, et al. (July 2009). "Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites". Science. 325 (5940): 612–6. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..612S. doi:10.1126/science.1175202. PMC 2803111. PMID 19644120.

- ^ Jia T, Pamer EG (July 2009). "Immunology. Dispensable but not irrelevant". Science. 325 (5940): 549–50. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..549J. doi:10.1126/science.1178329. PMC 2917045. PMID 19644100.

- ^ Angier N (August 3, 2009). "Finally, the Spleen Gets Some Respect". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2018-01-27.

- ^ Blackbourne LH (2008-04-01). Surgical recall. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-7817-7076-7.

- ^ "Penicilliary radicles". Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary (3rd ed.). Elsevier, Inc. 2007. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2011-04-03 – via The Free Dictionary by Farlex.

- ^ "Spleen: Information, Surgery and Functions". Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh - Chp.edu. 2010-11-17. Archived from the original on 2011-09-26. Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ^ Singh V (2017). Textbook of Anatomy Head, Neck, and Brain; Volume III (2nd ed.). Elsevier India. pp. 247–249. ISBN 9788131237274.

- ^ Yin C, Mohanta S, Maffia P, Habenicht AJ (6 March 2017). "Editorial: Tertiary Lymphoid Organs (TLOs): Powerhouses of Disease Immunity". Frontiers in Immunology. 8: 228. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00228. PMC 5337484. PMID 28321222.

- ^ a b Schumacher, Ton N.; Thommen, Daniela S. (2022-01-07). "Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer". Science. 375 (6576). doi:10.1126/science.abf9419. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Ruddle NH (March 2014). "Lymphatic vessels and tertiary lymphoid organs". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 124 (3): 953–9. doi:10.1172/JCI71611. PMC 3934190. PMID 24590281.

- ^ Hiraoka N, Ino Y, Yamazaki-Itoh R (2016-06-22). "Tertiary Lymphoid Organs in Cancer Tissues". Frontiers in Immunology. 7: 244. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00244. PMC 4916185. PMID 27446075.

- ^ a b c Teillaud, Jean-Luc; Houel, Ana; Panouillot, Marylou; Riffard, Clémence; Dieu-Nosjean, Marie-Caroline (September 2024). "Tertiary lymphoid structures in anticancer immunity". Nature Reviews Cancer. 24 (9): 629–646. doi:10.1038/s41568-024-00728-0. ISSN 1474-1768.

- ^ Goldsby R, Kindt TJ, Osborne BA, Janis K (2003) [1992]. "Cells and Organs of the Immune System (Chapter 2)". Immunology (Fifth ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. 24–56. ISBN 0-7167-4947-5.

- ^ Sato, Yuki; Silina, Karina; van den Broek, Maries; Hirahara, Kiyoshi; Yanagita, Motoko (August 2023). "The roles of tertiary lymphoid structures in chronic diseases". Nature Reviews Nephrology. 19 (8): 525–537. doi:10.1038/s41581-023-00706-z. ISSN 1759-507X. PMC 10092939.

- ^ Sautès-Fridman, C; Petitprez, F; Calderaro, J; Fridman, WH (June 2019). "Tertiary lymphoid structures in the era of cancer immunotherapy" (PDF). Nature Reviews. Cancer. 19 (6): 307–325. doi:10.1038/s41568-019-0144-6. PMID 31092904. S2CID 155104003.

- ^ van Hooren, L; Vaccaro, A; Ramachandran, M; Vazaios, K; Libard, S; van de Walle, T; Georganaki, M; Huang, H; Pietilä, I; Lau, J; Ulvmar, MH; Karlsson, MCI; Zetterling, M; Mangsbo, SM; Jakola, AS; Olsson Bontell, T; Smits, A; Essand, M; Dimberg, A (5 July 2021). "Agonistic CD40 therapy induces tertiary lymphoid structures but impairs responses to checkpoint blockade in glioma". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 4127. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.4127V. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24347-7. PMC 8257767. PMID 34226552.

- ^ a b Maoz A, Dennis M, Greenson JK (2019). "The Crohn's-Like Lymphoid Reaction to Colorectal Cancer-Tertiary Lymphoid Structures With Immunologic and Potentially Therapeutic Relevance in Colorectal Cancer". Frontiers in Immunology. 10: 1884. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01884. PMC 6714555. PMID 31507584.

- ^ a b Sautès-Fridman C, Petitprez F, Calderaro J, Fridman WH (June 2019). "Tertiary lymphoid structures in the era of cancer immunotherapy" (PDF). Nature Reviews. Cancer. 19 (6): 307–325. doi:10.1038/s41568-019-0144-6. PMID 31092904. S2CID 155104003.

- ^ Finkin S, Yuan D, Stein I, Taniguchi K, Weber A, Unger K, et al. (December 2015). "Ectopic lymphoid structures function as microniches for tumor progenitor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma". Nature Immunology. 16 (12): 1235–44. doi:10.1038/ni.3290. PMC 4653079. PMID 26502405.

- ^ Helmink BA, Reddy SM, Gao J, Zhang S, Basar R, Thakur R, et al. (January 2020). "B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures promote immunotherapy response" (PDF). Nature. 577 (7791): 549–555. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..549H. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1922-8. PMC 8762581. PMID 31942075. S2CID 210221106.

- ^ "lymphoid tissue" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Louveau A, Smirnov I, Keyes TJ, Eccles JD, Rouhani SJ, Peske JD, et al. (July 2015). "Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels". Nature. 523 (7560): 337–41. Bibcode:2015Natur.523..337L. doi:10.1038/nature14432. PMC 4506234. PMID 26030524.

we discovered functional lymphatic vessels lining the dural sinuses. These structures express all of the molecular hallmarks of lymphatic endothelial cells, are able to carry both fluid and immune cells from the cerebrospinal fluid, and are connected to the deep cervical lymph nodes. The unique location of these vessels may have impeded their discovery to date, thereby contributing to the long-held concept of the absence of lymphatic vasculature in the central nervous system. The discovery of the central nervous system lymphatic system may call for a reassessment of basic assumptions in neuroimmunology and sheds new light on the aetiology of neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases associated with immune system dysfunction.

- "NIH researchers uncover drain pipes in our brains". National Institutes of Health. October 3, 2017.

- ^ Kumar V (2018). Robbins basic pathology (Tenth ed.). Elsevier. p. 363. ISBN 9780323353175.

- ^ Vittet D (November 2014). "Lymphatic collecting vessel maturation and valve morphogenesis". Microvascular Research. 96: 31–7. doi:10.1016/j.mvr.2014.07.001. PMID 25020266.

- ^ Heppell C, Richardson G, Roose T (January 2013). "A model for fluid drainage by the lymphatic system". Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 75 (1): 49–81. doi:10.1007/s11538-012-9793-2. PMID 23161129. S2CID 20438669.

- ^ Bazigou E, Wilson JT, Moore JE (November 2014). "Primary and secondary lymphatic valve development: molecular, functional and mechanical insights". Microvascular Research. 96: 38–45. doi:10.1016/j.mvr.2014.07.008. PMC 4490164. PMID 25086182.

- ^ "The functions of the Lymphatic System". lymphnotes.com. Retrieved Feb 25, 2011.

- ^ Hu, Dan; Li, Long; Li, Sufang; Wu, Manyan; Ge, Nana; Cui, Yuxia; Lian, Zheng; Song, Junxian; Chen, Hong (2019-08-01). "Lymphatic system identification, pathophysiology and therapy in the cardiovascular diseases". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 133: 99–111. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.06.002. ISSN 0022-2828. PMID 31181226. S2CID 184485255.

- ^ Munn, Lance L.; Padera, Timothy P. (2014-11-01). "Imaging the lymphatic system". Microvascular Research. SI: Lymphatics in Development and Pathology. 96: 55–63. doi:10.1016/j.mvr.2014.06.006. ISSN 0026-2862. PMC 4268344. PMID 24956510.

- ^ Chong, Chloé; Scholkmann, Felix; Bachmann, Samia B.; Luciani, Paola; Leroux, Jean-Christophe; Detmar, Michael; Proulx, Steven T. (2016-03-10). "In vivo visualization and quantification of collecting lymphatic vessel contractility using near-infrared imaging". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 22930. Bibcode:2016NatSR...622930C. doi:10.1038/srep22930. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4785392. PMID 26960708.

- ^ Zhang, Yufan; Zhang, Juxiang; Li, Xiaowei; Li, Jingru; Lu, Shuting; Li, Yuqiao; Ren, Panting; Zhang, Chunfu; Xiong, Liqin (2022-06-01). "Imaging of fluorescent polymer dots in relation to channels and immune cells in the lymphatic system". Materials Today Bio. 15: 100317. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100317. ISSN 2590-0064. PMC 9213818. PMID 35757035.

- ^ Schineis, Philipp; Runge, Peter; Halin, Cornelia (2019-01-01). "Cellular traffic through afferent lymphatic vessels". Vascular Pharmacology. Pioneering updates in vascular biology. 112: 31–41. doi:10.1016/j.vph.2018.08.001. ISSN 1537-1891. PMID 30092362. S2CID 51955021.

- ^ Chavhan, Govind B.; Lam, Christopher Z.; Greer, Mary-Louise C.; Temple, Michael; Amaral, Joao; Grosse-Wortmann, Lars (2020-07-01). "Magnetic Resonance Lymphangiography". Radiologic Clinics of North America. 58 (4): 693–706. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2020.02.002. ISSN 0033-8389. PMID 32471538. S2CID 218943574.

- ^ Khan, A. R., Headland, S. E., Norling, L. V., & Lombardi, G. (2024). The emerging importance of lymphatics in health and disease: an update. *Journal of Clinical Investigation, 134*(1), e171582. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI171582

- ^ a b c Colledge NR, Ralston SH, Walker BR, eds. (2011). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh / New York: Churchill Livingstone / Elsevier. pp. 1001, 1037–1040. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7. OCLC 844959047.

- ^ Moore GE (May 1961). "Tumour cells and their spread". Can Med Assoc J. 84 (19): 1051–1053. PMC 1939597. PMID 13772299.

- ^ Douketis JD. "Lymphedema". Merck Manual.

- ^ Herantis Pharma (2015-07-21). "Lymfactin® for lymphedema". Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ Martín ML, Hernández MA, Avendaño C, Rodríguez F, Martínez H (March 2011). "Manual lymphatic drainage therapy in patients with breast cancer related lymphoedema". BMC Cancer. 11 (1): 94. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-11-94. PMC 3065438. PMID 21392372.

- ^ Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper D, Hauser S, Longo DL (19 March 2009). Harrison's Manual of Medicine. McGraw Hill Professional. pp. 352–. ISBN 978-0-07-147743-7. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ambrose CT (July 2006). "Immunology's first priority dispute--an account of the 17th-century Rudbeck-Bartholin feud". Cellular Immunology. 242 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.09.004. PMID 17083923.

- ^ a b c d e Flourens P (1859). "Chapter 3: Aselli, Pecquet, Rudbeck, Bartholin". A History of the Discovery of the Circulation of the Blood. Rickey, Mallory & company. pp. 67–99. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

william harvey.

- ^ Natale, Gianfranco; Bocci, Guido; Ribatti, Domenico (September 2017). "Scholars and scientists in the history of the lymphatic system". Journal of Anatomy. 231 (3): 417–429. doi:10.1111/joa.12644. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 5554832. PMID 28614587.

- ^ a b Eriksson G (2004). "[Olaus Rudbeck as scientist and professor of medicine]". Svensk Medicinhistorisk Tidskrift (in Swedish). 8 (1): 39–44. PMID 16025602.

- ^ "Disputatio anatomica, de circulatione sanguinis" [Account of Rudbeck's work on lymphatic system and dispute with Bartholin]. International League of Antiquarian Booksellers. Retrieved 2008-07-11. [dead link]

- ^ "Chapter 25, "Galen in an Age of Change (1650–1820)", Maria Pia Donato". Brill's companion to the reception of Galen. Petros Bouras-Vallianatos, Barbara Zipser. Leiden. 2019. ISBN 978-90-04-39435-3. OCLC 1088603298.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Mitchell, Peter (2007). The Purple island and anatomy in early seventeenth-century literature, philosophy, and theology. Madison [NJ]: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-8386-4018-0. OCLC 65207019.

- ^ "Galen | Biography, Achievements, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ Turner AL (1937). Story of a Great Hospital: The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh 1729-1929. Oliver and Boyd. p. 360.

- ^ "Two UVA Findings in the Running for Year's Biggest Scientific Breakthroughs | UVA Today". news.virginia.edu. 2015-12-03. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ lympha. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- ^ "lymph". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

External links

[edit]- Lymphatic System

- Lymphatic System Overview (innerbody.com)